For decades, cultural critics and marketers relied on a dependable formula: the 20-year nostalgia cycle. The 1970s were obsessed with the ’50s (think Grease and Happy Days). The ’90s brought back the ’70s bell-bottoms. By the 2000s, we were deep in an ’80s synth-pop revival. It took roughly two decades for a generation to grow up, gain disposable income, and look back fondly on their childhood aesthetics with rose-tinted glasses.+1

That rule is dead.

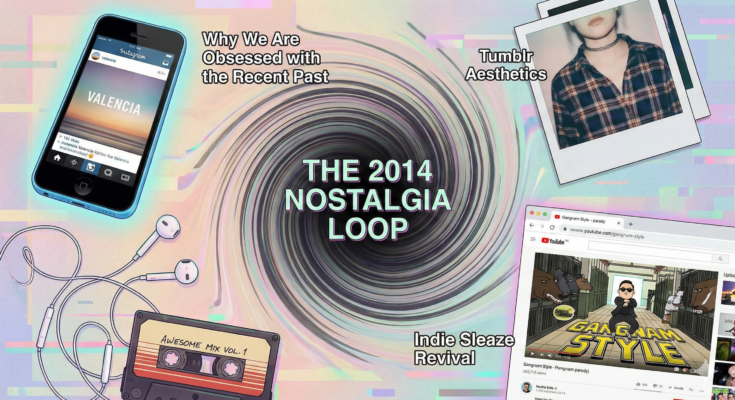

Welcome to the accelerated timeline of the digital age, where the distance between “the present” and “the golden past” has collapsed dramatically. We are currently in the grip of a fierce nostalgia for the mid-2010s—specifically, the era around 2014.

It was a time of peak Tumblr grunge aesthetics, the Valencia filter on Instagram, American Apparel disco pants, and the chaotic energy of “indie sleaze.” But why are we pining for a period that happened only ten years ago? The answer lies in how the internet has fundamentally broken our perception of time and accelerated the metabolism of culture.

The Aesthetic Nostalgia of 2014

To understand the 2014 nostalgia loop, we first have to identify what is being resurrected. It isn’t a monolithic culture; it’s a specific digital vibe that older Gen Z and younger Millennials are curating.

If you scroll through TikTok or look at current Depop trends, the markers of 2014 are everywhere. It’s the return of wired headphones as an accessory. It’s the gritty, flash-on photography style reminiscent of a hazy Cobra Snake party photo. It is the sonic backdrop of The 1975, Arctic Monkeys’ AM era, and Lana Del Rey’s Ultraviolence.

This was the peak era of the “curated internet persona,” before the hyper-polished influencer economy fully took over, yet after the raw innocence of the early web died. It was the age of the “sad girl” Tumblr aesthetic—a stylized melancholy that feels almost quaint compared to the genuine climate and political anxiety of the 2020s.

The Engine of Acceleration: Why the Cycle Shrank

Why has the 20-year cycle shrunk to ten? The primary culprit is the sheer velocity of the modern internet.

In the pre-digital era, trends moved slowly through magazines, MTV, and physical retail stores. A subculture needed time to gestate, peak, die out, and stay dead long enough to become “vintage.”

Today, thanks to algorithmic feeds on TikTok, Instagram Reels, and X (formerly Twitter), trends are born, saturated, and discarded in a matter of weeks, sometimes days. We consume culture at a hyper-accelerated rate.

Because we metabolize the present so quickly, the “past” arrives sooner. A meme from three years ago already feels ancient because we have lived through ten thousand micro-trends since then. The digital distance between 2024 and 2014 feels vastly wider than the physical distance of ten years. We haven’t just lived a decade; we’ve lived through several lifetimes of digital evolution.

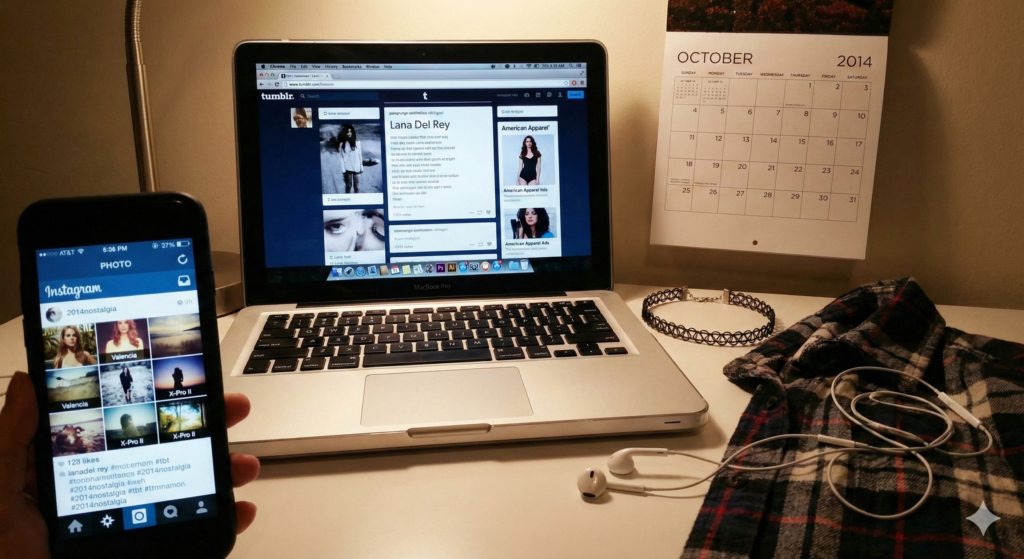

Furthermore, the internet serves as a perfect, instantly accessible archive. We don’t need to wait for a VH1 “I Love the 2010s” special to remember what we wore. Our own digital footprints—our old Instagram posts and Timehop reminders—serve the past back to us daily. We are constantly confronted with who we were ten years ago, making it easier to romanticize that version of ourselves.

Seeking Shelter in the “Simpler” Mobile Web

Nostalgia is rarely about the actual past; it is about using a stylized version of the past as a comfort blanket against the anxieties of the present.

Looking back at 2014 from the vantage point of 2024 offers significant psychological safety. The mid-2010s represent the last gasp of the “pre-pandemic” world. It was a time before the extreme political polarization of 2016 onwards, before COVID-19 redefined social interaction, and before the looming existential dread of AI.

Crucially, 2014 was a sweet spot in technological adoption. We had iPhones and high-speed mobile internet—we were connected—but the algorithms hadn’t yet completely gamified our attention spans. Instagram was still mostly just chronological pictures of your friends’ brunch, not a shopping mall disguised as a video feed.

The nostalgia for 2014 is a yearning for a time when the internet felt like a place you visited, rather than a place you lived. It feels, in retrospect, like a simpler digital age.

The Future of Memory

The 10-year nostalgia loop suggests a strange future for culture. If the timeline continues to compress, will we soon be nostalgic for the trends of 2020? Will “pandemic-core” become a vintage aesthetic in 2026?

The obsession with the recent past indicates a culture suffering from future fatigue. When the road ahead looks daunting, the rearview mirror becomes mesmerizing. By speed-running history and mining the immediate past for aesthetic content, we are creating a feedback loop where nothing truly ever goes away—it just waits in the digital archive for its turn to be trending again.

Here are three additional sections to expand the article, along with a final conclusion, seamlessly continuing the cultural commentary.

The Commercialization of Micro-Nostalgia: Fast Fashion’s Time Machine

The shrinking timeline of our cultural memory isn’t just a psychological phenomenon; it is a highly profitable business model. In the era of the 20-year cycle, so it took time for vintage stores to curate collections and for designers to reinterpret past decades for the runway. Today, the supply chain is as fast as the internet.

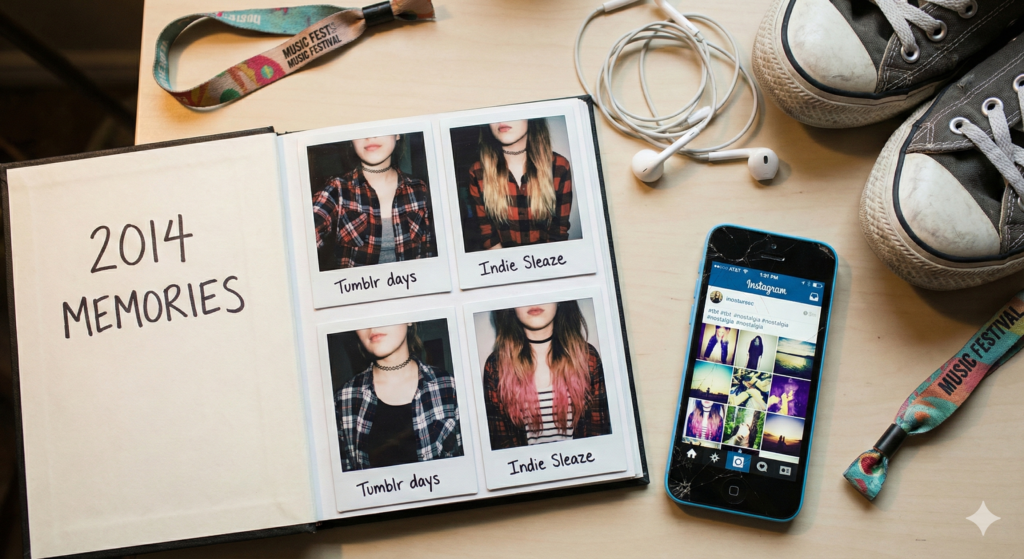

Enter the commercialization of micro-nostalgia. Ultra-fast fashion giants and algorithmically driven retailers act as instantaneous time machines. So, the moment a TikTok creator goes viral for romanticizing 2014 “Tumblr grunge” or indie sleaze, factories are spinning up production on velvet skater skirts, grid-print flannels, and exact replicas of the era’s signature chokers.

We no longer have to hunt for vintage pieces in thrift stores to participate in a revival. The recent past is immediately repackaged, mass-produced, and sold back to us at lightning speed. This hyper-commercialization acts as gasoline on the fire, thus ensuring that the moment we feel a twinge of longing for a decade ago, there is a “Buy Now” button waiting to fulfill it.

Streaming Services and the Manufactured Nostalgia Trap

It isn’t just our wardrobes that are stuck in the recent past; our entertainment diets are heavily curated to keep us looking backward. So, streaming platforms and media conglomerates have realized that tapping into the 2014 era is a guaranteed way to drive engagement without the financial risk of launching entirely new intellectual properties.

We are currently living in the era of the “instant reboot.” Franchises that barely had time to gather dust—like The Hunger Games, Pretty Little Liars, or the peak-2010s dystopian YA genre—are being revived, spun-off, or heavily promoted on streaming front pages.

Even our music apps are complicit. Features like Spotify Wrapped and algorithmically generated “Time Capsule” playlists constantly feed our past listening habits back to us. We are rarely forced to discover the new because the platforms we rely on are so incredibly efficient at trapping us in a cozy, manufactured loop of our own recent history.

Gen Alpha and the Bizarre Rise of Borrowed Memories

Perhaps the most fascinating element of the 2014 revival is who is actually participating in it. It isn’t just older Gen Z and Millennials reminiscing about their high school or college years. A massive driver of this trend is Gen Alpha and younger Gen Z—kids who were literal toddlers in 2014.

There is a word for this: anemoia, which means experiencing nostalgia for a time you never actually lived through.

To a teenager in 2024 or 2026, the mid-2010s look like a digital utopia. They view 2014 exclusively through the highly curated, surviving artifacts of Tumblr mood boards, YouTube vlogs, and Pinterest aesthetics. Are nostalgic for the idea of 2014—a time they perceive as having the fun of the internet without the crushing weight of the modern influencer economy, algorithmic doom-scrolling, or current global anxieties. So, they are borrowing memories to escape their own present.

Conclusion: Escaping the Present Tense

The 2014 nostalgia loop forces us to ask a difficult question: Are we moving forward, or are we just scrolling backward?

The fact that our cultural nostalgia cycle has aggressively shrunk from twenty years down to a mere ten is a symptom of a society experiencing severe digital whiplash. So, the modern world moves so fast, and the future feels so overwhelmingly unpredictable, that the present tense has become deeply uncomfortable.

Thus, in response, we use the internet as a cultural panic room. We retreat into the recent past—re-wearing the clothes, re-listening to the indie sleaze anthems, and adopting the aesthetics of 2014—because it is a story where we already know the ending. It feels safe. But as we continue to mine yesterday for today’s content, we risk losing the ability to create anything genuinely new. If we are always looking in the rearview mirror, we might just forget how to drive forward.